Measuring impact and building evidence are important for so many reasons. It keeps us honest to our mission, helps us learn and grow, and offers insights into how best to deploy our resources and efforts for meaningful change. Are we moving closer to our chosen horizon? How do we know?

Despite good intentions, traditional impact measurement frequently falls short— including in the field of global mental health. Impact frameworks are often too narrowly focused on disease reduction or short-term symptom improvement, while missing the critical benefits that matter in local communities and contexts.

At Brio, we believe impact measurement processes should be both rigorous and dignifying for everyone involved. This requires acknowledging the challenges facing common approaches to impact measurement, and finding ways to improve it.

But first— who is impact measurement for?

We believe that data should be useful to all stakeholders. Governments, funders, collaborators, implementers, and participants all care about different kinds of data points.

Yet, it’s not uncommon in our field to hand off impact measurement to research experts, who often represent only one perspective amongst many stakeholders involved. Evaluation approaches that take a too-narrow understanding of the intended outcomes fall into several traps.

- They assume they know what success looks like going in: for example, a strictly disease-oriented approach misses many possibilities, such as experiencing change and vitality while living with a disease.

- They at times ignore what participants actually care about and whether the narrow definition of success (and the program) meaningfully corresponds to communities’ needs and hopes for everyday life.

- They seek to generalize where generalization doesn’t always help: mental health promotion needs more cultural nuance than a flu vaccine in order to be effective, and therefore success must be defined by context, while elevating common threads across contexts.

Furthermore, organizations may experience pressure to align their measurement strategies with what funders have already identified as the outcomes they want to see. While it makes sense for funders to seek proof of meaningful impact, that impact comes from a deep understanding of the context, the field of work, and the range of potential positive changes that communities find most compelling. Participants might move up or down a scale, but we must remember that whether any change is positive is subjective— and therefore, participants must weigh in on whether the change we measure is the change they care most about.

After all, programs should benefit participants in ways that participants themselves can notice, name, and ultimately enjoy— otherwise, what are we all doing?

So how do we measure impact better, so that everyone involved is learning and growing? How do we do so while balancing the burden of heavy data collection, especially on communities already marginalized?

Collaboratively defining success in mental health promotion

In order to measure change effectively in a quantitative way, we have to define what success looks like. In mental health, as in much of the field of health, the reduction of disease has been a common focus. Input: symptoms of disease; output: fewer symptoms of disease.

While reducing suffering is a worthy goal, mental health is much more than the absence of suffering. As such, finding ways to capture the real-life improvements that programs and interventions make possible is all the more important— and must be collaborative.

In particular, mental health promotion is the process of helping individuals and communities strengthen the underlying inner processes and skills that improve mental health. At Brio, we use the construct of psychological flexibility, promoted by the well-researched mental health intervention Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). ACT has more than 1000 randomized controlled trials supporting its effectiveness across a wide range of populations. Learn more here.

But, if we’re aiming for more than just the reduction of disease, then what are mental health skills for? Our theory of change is that if people strengthen their psychological flexibility, it enables them to do more of what matters to them— even if difficult life circumstances continue. Psychological flexibility improves mental health so that individuals have more agency: it expands the range of circumstances in which they are free to choose their next action.

Thus, as a behavioral intervention, ACT as a promotion strategy necessitates understanding what kinds of behavioral changes are important to participants. In other words, what makes everyday life worthwhile? How might we help you do more of that?

Two key pillars in our evaluation philosophy

Elevating participant priorities while remaining accountable to all other stakeholders requires a balancing act. Integrating multiple perspectives into the impact measurement approach can come at a cost— the more questions and processes we integrate, the more time and resources required. We seek to strike the balance between comprehensive data and burden-free data using two key principles.

1) We focus on developmental evaluation (in contrast to summative), designed to answer key process and outcomes questions that help us to improve the quality of our programs. Developmental evaluation captures impact in a way that is not intended to cement in stone a process or mechanism, but rather to understand what changed, and how to do more of it. This posture of learning also acknowledges that as programs, initiatives and ideas scale to other contexts or are delivered by new implementors, they will need to adapt to those circumstances. What we learn with a developmental posture can be applied more effectively to adaptation than a rigid protocol that requires full fidelity in order to work.

All too often, practitioners, researchers, and even funders feel pressure to prove that something “works” beyond a doubt— which disincentivizes transparency. Learning and course-correction are critical to innovation and evolution, and more frequently the reality of implementation, than rigidity.

2) We conduct participatory research design. We believe that if we are asking participants to give us their time and their data that it should be as helpful to them as possible. We consider participant input on what outcomes matter to them, what kinds of questions resonate, and factor in the cost-benefit tradeoff for adding more questions to a survey. Interviews are reflective and lead to self-discovery rather than focus on extracting quotes we can use. We seek to learn alongside participants rather than solely prioritize our need for numbers to report.

This is why, in addition to using “validated” scales (more on that below), we listen deeply to identify what participants want out of the program. What would make this worth their while? What changes do they want to see? And we consider broad questions that reflect these intentions in our evaluation methods.

Examples might include:

- How frequently are girls speaking up and expressing themselves in the classroom?

- Do young social change leaders feel a sense of community care and self- and other-awareness in their work?

- To what extent do Rohingya refugee women take action to help their neighbors access resources?

- Can youth in gang-affected neighborhoods identify their values and steps to take action in the midst of social pressure?

- Are educators implementing positive mental wellbeing practices in their own lives?

Finding the right scales: validated across contexts, or create your own?

When it comes to choosing scales to measure change, there are certainly benefits to using scales that other organizations have used. It allows for comparison and a shared vocabulary. We have utilized scales that make sense given the goals of the mental health promotion program and what participants have shared is important to them.

Critically, it’s important to test every scale with a small group of participants before deploying it— and to be clear about why you’re using it. Do the questions make sense to them? Can they answer them in a way that reflects their real experience?

Some useful scales that we’ve considered or deployed include:

- WHO-5 Wellbeing Index

- Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale

- Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II

- WELLBYs (Wellbeing Adjusted Life Years)

The challenge with “validated” scales is that they may have good general statistical properties, but they may not capture all the specific impact that a program has. Limiting impact measurement to scales that others have developed and used is decidedly not sufficient for our standard of participatory research design.

And not all “validated” scales will work for all contexts. It’s really difficult to develop these when you’re measuring not for the absence or reduction of symptoms (disease orientation), but rather for life improvement— which is highly subjective.

While we have used scales to measure psychological flexibility itself, which we believe underpins effective mental health promotion, not all populations (e.g., children and youth in various contexts) are able to answer these questions given their developmental state and cultural-linguistic exposure to these concepts. Their daily experiences and behaviors are a better indicator of whether they’ve learned these skills.

Case study: developing a scale for children in Rajasthan

In 2021, we worked with our partners Kshamtalaya on this challenge— how do we capture the change we’re seeing in children in primary schools in the state of Rajasthan?

Working with implementers, teachers, and children themselves, we created an assessment that measured effort-based self-efficacy. We started with the question: what does it look like when a child is thriving in this context? And we narrowed it down to a set of common behaviors that the child would find easy to do if they had these underlying skills.

After testing and refining, the measure holds internal validity and reflects children’s lifeskills capacities including self-expression, self-awareness, and self-in-community. Children were able to answer this short set of questions on their own, with limited support from a trained facilitator— and we’ve been able to measure program impact, such as Khushi Shala pilot, using this scale.

Analysis: a rigorous approach to understanding results and learning from them

Our data analysis process

Once data is collected, it’s important to analyze them with rigor and transparency. While the collection process and philosophy is flexible and participant-focused, once we have collected the data it becomes a highly structured process. Drawing upon over a decade of experience in elite research university psychology labs and real world experience, our team utilizes the appropriate methods and tests for the data we collect. Data is analyzed in statistics software and results reported with a rigorous level of accuracy and transparency. We believe that data analyzed this way helps us all to learn because of the high degree of confidence it gives us in our findings. Ultimately we do it this way because we feel it best honors our participants who trusted us to use their data well.

The problem with “average % change”

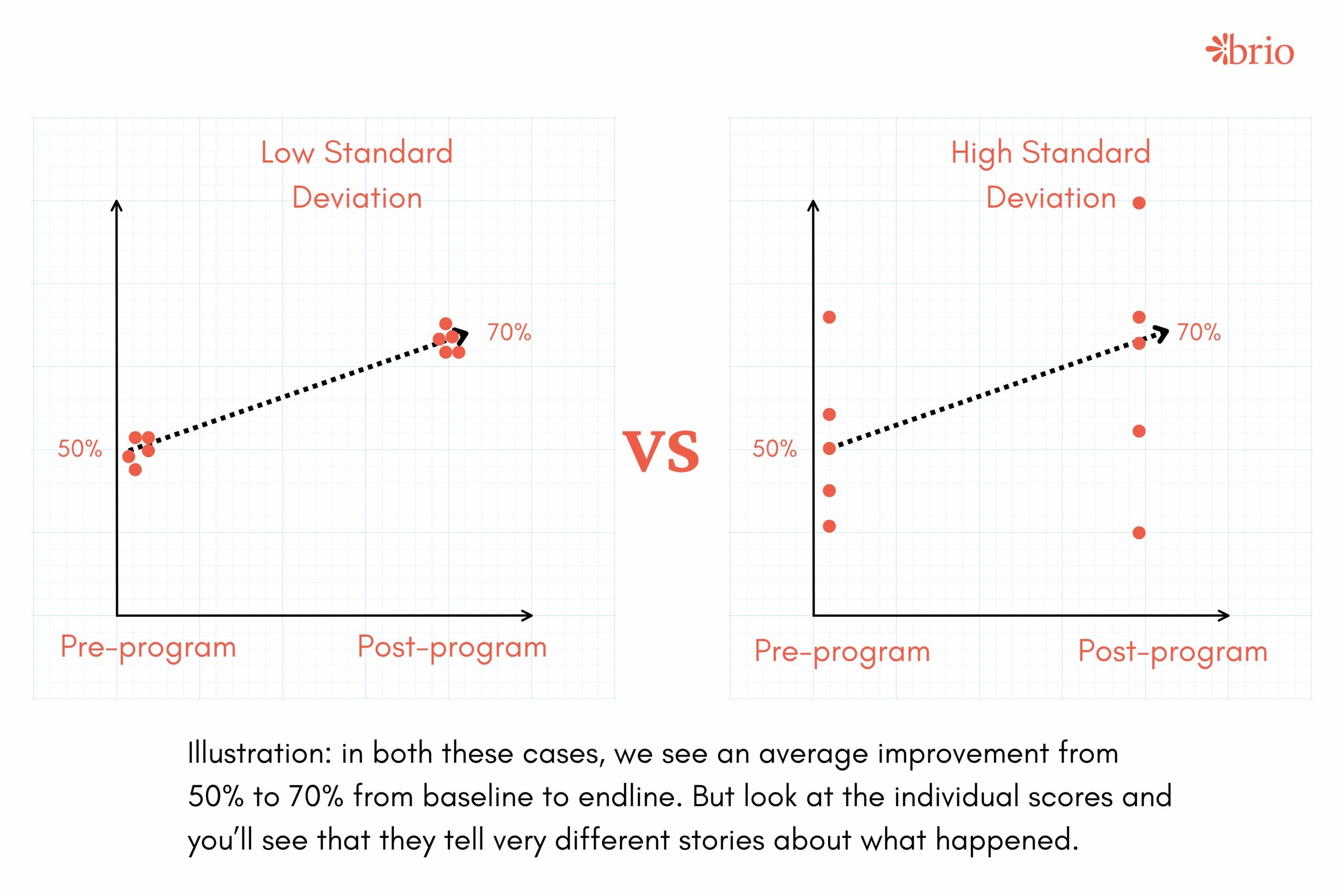

Too many program evaluations take the group average at the beginning and end, and as long as the trendline is upward, they conclude that the program was successful. But the problem with this approach is that it doesn’t tell you what really happened and for whom the program was impactful. For instance, if the average on a scale went from 50% to 70%, it’s possible that some participants improved marvelously while a majority actually got worse!

Instead of just the average, we want to know both the significance and the meaningfulness of differences. The average change (e.g. 20% improvement) doesn’t account for random chance and normal variation. Statistical significance tells us the change isn’t due to chance, but it can still be achieved for meaningless results (e.g. a 0.5% decrease in depression). We need to establish that changes are meaningfully large too.

Here’s a brief overview of how we use statistical analysis to understand participant pre-to-post program data:

1) We look for statistical significance. Significance tells us if the change is ‘real’ or if it’s all just random chance. To calculate statistical significance, we need quality data from enough participants— statistical power is based on the type of analysis you want to run. The more complex the analysis, the more participants you need.

2) We compare everyone’s pre-test score with their post-test score to find the real change. Group averages from pre to post test are useful, but they don’t tell the full story. Instead, we look at what happened on the individual level. This approach allows us to be more confident in the results because it compares individuals to themselves and instead of flattening nuances with a group average.

When we compare individuals to themselves, we also measure the standard deviation of all the individual changes observed. It all comes together to let us calculate effect size. This tells us not just if there is a change, but if the change is large enough to be meaningful. We like to use Cohen’s d.

d = mean of differences / standard deviation of differences

Why effect size matters

When a program is reporting a key outcome (for example, that a percentage of participants are disease-free post program), it’s hard to know how meaningful that difference is at the individual level. Did it require one small improvement to pass the threshold— or did the program contribute to a lot of change? Effect size in a sample can help answer this question.

At the same time, expected effect sizes vary by the intensity of the intervention. You could reasonably expect a different effect size from highly-individualized treatments (like one-on-one therapy) than from broad-reaching social interventions and programs. High-cost interventions should yield higher effect sizes to meaningfully justify the cost, while high-quality low-cost interventions can yield smaller effect sizes and still be highly meaningful because of the breadth of cost-effective impact.

Isolating variables to learn more

With linear equation modeling, it’s possible to learn more about what impacted a variance in outcomes if that information is collected and corresponded to each individual data. To go deeper we control for other variables: location, gender, facilitator, etc. Did one community experience a disruption that another community did not? Were there logistical hurdles, or were certain facilitators stronger than others? How does gender or another identity affect how the program impacted the participant?

Again, this is useful from a developmental evaluation perspective, because it allows us to learn even more from the data and implement any changes and improvements that might be needed to see even higher benefits to all participants.

Just as critical: storytelling and participant voice

Practiced well, participant storytelling is not just a euphemism for getting nice program quotes. As we integrate a liberation psychology lens into everything that we do, storytelling (or testimonios) is another way for participants to define success for themselves and share what did and didn’t work in the program.

Furthermore, verbalizing and expressing the change that we experience actually facilitates a meaningful process of internalizing that change for ourselves. Elevating participant voice expands agency as well— all of which are important to the broader mission of helping individuals and communities do what matters to them.

When we worked with Rohingya refugee women in Malaysia, many of them were surprised that we asked for their feedback. As a group protected by the UNHCR, they’ve experienced many programs delivered that were intended to benefit them. But none of those programs allowed them to speak, according to one of the community leaders. “This was the first program where we were allowed to share what we really think,” she said.

Yes— the bar is that low sometimes. So while some participants may not want to answer more questions, many might appreciate and even cherish the opportunity. And we get to benefit from their insight and wisdom.

Can impact measurement be liberatory and not oppressive?

Impact measurement can be used as an exercise of external power, or a process of liberation and community expression. We think the latter actually achieves the aims of everyone: ensuring that the most meaningful change is captured, and that the people who engage in the program achieve what’s important to them.

It facilitates learning for everyone else as well— governments, implementors, funders and partners benefit immensely from knowing what truly worked, what can be improved, and which approaches should be adopted as policy, implemented at scale, or refined for improvement.

Implementing organizations can also be freed from pressuring participants to give them the results that they think funders want to see. By letting go of the burden of showing a rip-roaring success every time, a developmental, collective learning process shows humility, upholds dignity, and ultimately makes the most meaningful change possible.